Last week, we explored the history of American probation, from John Augustus to Martinson’s course altering “What Works? Questions and Answers About Prison Reform,” before finally digging into policy changes in the 80s and 90s that laid the groundwork for modern probation.

Missed last week? You can read our three-part series on probation history here – Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

Here’s a quick synopsis before we move on.

Probation in the US was created to be an alternative to incarceration and enable the individual to stay in their community. At the state level, America didn’t have a formal probation system until the mid-1800s, and it wasn’t until 1956 that every state had both adult and juvenile probation programs. Federal probation rolled out in 1925. Until the 1970s, probation programs—federal and state—were based on a rehabilitative model. Then, in 1974, Robert Martinson published “What Works?” and concluded that the rehabilitative model was not effective. His arguments fell on fertile soil. The rehabilitation model of probation was rapidly discarded and replaced with a compliance and surveillance (C&S) based model. The legacy endures and today many probation programs continue to follow a C&S model.

Modern Probation

“Nationwide, on any given day, more people are on probation than in prisons and jails and on parole combined.”

The Pew Institute

At the end of 2018, 3.5 million—1 in 72—individuals were on probation in the US. The majority of those individuals are being supervised under the C&S model of probation introduced after Martinson’s 1974 article. However, rather than being an alternative to incarceration as intended, a growing body of research shows that probation has become a driver of incarceration.

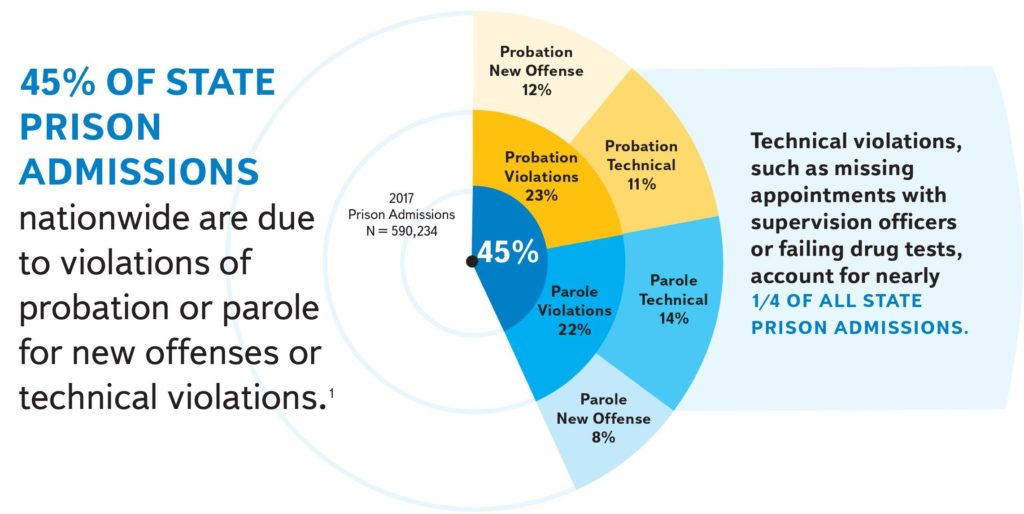

A 2019 analysis of state prisons found that “45% of state prison admissions nationwide are due to violations of probation or parole.” A quarter of those admissions are due to technical violations for things like missing scheduled appointments with probation staff, being out after curfew, not paying supervision fines, or failing a drug test. What that means is that each day 280,000 people are in prison because of a supervision violation.

Bluntly, probation is not having the desired result. But why? Research has identified specific probation components that exacerbate cycles of recidivism and incarceration. There are others, but we’re going to focus on five primary probation components that research shows are problematic.

Excessive Rules

People on probation are expected to follow specific rules. If they don’t, their probation can be revoked. However, analysis shows that having too many rules “make[s] it difficult for many people on probation and parole to keep a job, maintain stable housing, participate in drug or mental health treatment, or fulfill financial obligations.”

Common rules include:

- Reporting in person to probation offices

- Participating in intensive supervision programs

- Not leaving the designated city/state without permission

- Finding and maintaining regular employment

- Not changing residence or employment without permission

- Not using drugs or alcohol; not entering drinking establishments

- Not possessing firearms or other dangerous weapons

- Not associating with persons who have criminal records

- Submitting to urinalysis or blood testing when instructed

- Paying supervision fees

- Obeying all state and local laws

Want to see specific probation rules? Check out the rules for NC, Western VA, Multnomah County OR, and Federal Probation.

Inappropriate Supervision Levels

Analysis shows that using intensive supervision methods with low-risk individuals is more harmful than no supervision and increases the risk of recidivism without promoting public safety. Unfortunately, many programs do not use a validated assessment tool to assess risks and needs. As a result, inappropriate supervision continues in many probation programs.

Inadequate Treatment

SAMHSA estimates that 70 percent of individuals involved with the criminal system “have a substance use disorder, and approximately 17–34 percent have [a] serious mental illness.” However, despite the need and efforts to improve treatment access, many individuals in the probation system do not have access to the treatment they need, which contributes to poor program outcomes.

Long Probation Terms

In a 2020 analysis of probation, the Pew Institute concluded “two main factors have driven growth in the community corrections population: the number of people sentenced to probation and parole, and the length of time they remain under supervision.” Adding that an increasing number of studies show that “long probation sentences are not associated with lower rates of recidivism and are more likely than shorter ones to lead to technical violations,” leading to sanctions, revocations, and incarceration. The Pew Institute goes on to recommend that to “be effective, probation systems should prioritize resources for the period during which a person is most at risk to re-offend, typically the first 12 to 18 months.”

Overextended Probation Staff

The demand for supervision and the number of individuals on probation have both swelled, but the support for probation programs has not kept pace. One Harvard study points out that “probation is the most severely underfunded” criminal justice agency in America, which has contributed to severely overextended program staff. Overextended staff have less time to devote to high-risk individuals and less time to connect the individuals “who are most likely to fail on supervision” to the resources they need. Studies show that “even when policy requires the use of evidence-based practices, implementation can suffer if supervision agents are overloaded.”

“Nothing is wrong with probation. It is the execution of probation that is wrong.”

These are not small issues and might leave some asking, “is probation hopeless?” By no means. Join us next week as we look at how these issues are being addressed and how Reconnect is building a platform to help.

UP NEXT IN JANUARY

Probation in America

Don’t miss the final installment of our month-long exploration of probation in the United States, right here!

A Fireside Chat with Chief Wendy Still

Our CEO Sam Hotchkiss is kicking off Reconnect’s 2021 Webinar series with a one-on-one conversation with Wendy Still, Chief Probation Officer of Alameda County (Oakland, CA) and former Chief Probation Officer of San Francisco county as she prepares to retire later this year.

During her career, she has witnessed drastic policy shifts, the evolvement of effective evidence-based strategies and practices, budget and staffing cuts, and countless other industry milestones, while being a relentless advocate for change and progress within the system.

When: January 28 at 4 PM ET

Spaces for the chat are limited and filling up fast, register now!